Specialty films find more receptive studios

By Lorenza Munoz

Los Angeles Times

04-21-2005

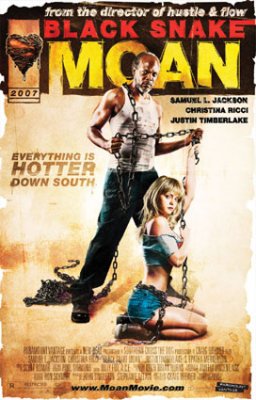

Director Craig Brewer is so hot that two studios are willing to pay more than $10 million for his film Black Snake Moan.

Nevermind that he has yet to shoot a frame of film. Or that the plot involves a white nymphomaniac who must be "cured" of her disorder by an older black bluesman.

"Would the script that I’ve written been considered last year? Absolutely not," he says. "There might be a change in the way Hollywood thinks about challenging movies."

Filmmakers such as Brewer are riding a seller’s market. Enticed by the potential returns and prestige that specialty movies generate, studios are scouring film festivals and screening rooms for the next Sideways or My Big Fat Greek Wedding. Executives are willing to pay as much as $25 million for movies that only a few years ago would have fetched half as much. Some movies even come with top stars willing to take pay cuts for a taste of the genre’s cachet.

"There is a new nexus between specialized film, new money, mainstream Hollywood stars and power," says United Talent Agency agent Jeremy Barber. "To think of these movies outside of mainstream Hollywood is an anachronistic view."

Never have there been more big players in the specialty movie world. Such films are typically made on low to moderate budgets with scripts that are mainly character-driven. Once confined to art-house theaters, they now play in multiplexes alongside summer blockbusters. For studios, a genre that once brought more prestige than profits has become integral to their business strategies.

The godfathers of the independent film business, Bob Weinstein and Harvey Weinstein, recently finalized their split with Walt Disney Co., which bought their Miramax Films in 1993. The brothers will form another specialty film company, leaving Disney to retool Miramax. Another deal came last month when Time Warner Inc.’s HBO Films and New Line Cinema joined to buy Newmarket Films, distributor of The Passion of the Christ.

That increasing competition is bad news for studios writing the checks, good news for people such as Brewer. He came away from the Sundance Film Festival in January with $9 million for his first movie, Hustle & Flow.

Every major studio is putting its financial and marketing weight behind its specialty film divisions. News Corp.-owned 20th Century Fox’s Fox Searchlight has become a gem for the company. NBC Universal’s Focus Features has become a major player, while Warner Bros. is moving its Warner Independent Pictures into high gear. Viacom Inc.’s Paramount Pictures executives are making the revamping of Paramount Classics a top priority. Sony Corp.’s Sony Pictures Entertainment is reviving its TriStar label as a specialty film unit.

Then there are industry outsiders with fat wallets, including billionaires Mark Cuban and Philip Anschutz, who have caught the specialty film bug by bankrolling movies.

On the financing side, investors are increasingly willing to put their money into these films. One reason is that studios are lowering the risk by allowing investors to recoup money by sharing in lucrative DVD sales, says John Sloss, founder of Cinetic, a film financer and consultant.

"That helps people ... make rational business decisions," Sloss says. "It’s getting more and more attractive."

Endeavor agent John Lesher says some specialty films had become a much easier sell. Two years ago, he couldn’t interest a single studio in backing The Motorcycle Diaries, a film set in South America and directed by his client, Oscar-winning director Walter Salles. Focus Features eventually bought it at Sundance, and the film went on to win an Academy Award for best song.

"Back then, everyone here took a wait-and-see attitude," Lesher says. "Today, everyone would want it from a screenplay level."

A genre that used to attract mostly up-and-coming actors and directors now can more easily get box-office insurance in the form of stars. Danny Green had trouble pitching The Tenants, based on Bernard Malamud’s novel.

Finally, Dylan McDermott, who starred in ABC’s long-running drama The Practice, came on board, joined by rap star Snoop Dogg. Financier Avi Lerner invested more than $850,000. The film will debut at the Tribeca Film Festival later this month.

"Hollywood respects the fact that these films do have an audience," Green says.

Ryan Murphy created the hot cable TV show Nip/Tuck but had never directed a feature. That didn’t stop Annette Bening, Gwyneth Paltrow and Joseph Fiennes from taking pay cuts for Murphy’s Running With Scissors, a drama about a dysfunctional family based on the best-selling memoir by Augusten Burroughs.

Murphy had several studio offers to make the film, but he went with TriStar, whose top executive, Valerie Van Galder, was one of the creative brains behind Sony’s Adaptation and Fox Searchlight’s The Full Monty. Running With Scissors, which is in production, is budgeted at $12 million.

Murphy acknowledges that having a strong cast makes it easier.

"When you walk in with as many elements as you can, then (studio executives) see the movie, not just a script," he says.

The biggest check for a specialty film this year came from Paramount Pictures, which paid a whopping $25 million for director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s latest project, Babel — a dark drama spoken mainly in foreign languages.

Granted, the cast of Babel includes box-office star Brad Pitt. But Pitt stipulated that he did not want Babel marketed as a Brad Pitt movie.

Industry veterans warn that the landscape is in transition. For every new specialty film label, smaller ones that can’t compete are going out of business or being swallowed up.

But the new blood is a boon for people such as Christine Vachon. The producer is preparing Every Word Is True, based on Truman Capote’s relationship with the two killers in his book In Cold Blood, for Warner Independent.

"The more players there are," Vachon says, "the better off we all are."